2. 青岛市市立医院内分泌科

EB病毒(EBV)是最早发现的人类肿瘤相关病毒,在人群中广泛存在,全球约有95%以上的人感染EBV[1-2]。已有研究证实,EBV与多种肿瘤有密切关系,尤其是淋巴细胞源性和上皮细胞源性恶性肿瘤,如胃癌、鼻咽癌、淋巴瘤等[3-4]。胃癌是严重威胁人类健康的恶性肿瘤,预后差,复发转移率高[5-6]。EBV相关胃癌(EBVaGC)约占胃癌的10%,是除微卫星不稳定性胃癌、基因组稳定胃癌和染色体不稳定性胃癌之外的一个特殊胃癌亚型[7-10]。微管相关蛋白(MAPs)是一类与细胞骨架微管相互作用的蛋白质,细胞中某些MAPs的异常表达能够引起微管动态系统的失衡,在肿瘤的发生发展过程中起关键作用[11-12]。微管相关蛋白9 (MAP9)是一种细胞周期相关的微管蛋白,定位于有丝分裂纺锤体,在双极纺锤体组装和有丝分裂的过程中起关键作用[13]。MAP9表达异常会导致纺锤体异常,从而引起染色体集合和分离出现错误,形成非整倍体细胞,被认为是肿瘤的特征之一[14]; 而抑制MAP9表达可形成多极纺锤体,使有丝分裂延迟,引起胞质分裂失败或细胞死亡[15]。因此MAP9异常表达与肿瘤的发生密切相关,但是迄今为止尚未有病毒感染与MAP9相关性的研究报道[16]。前期研究发现,EBV阳性胃癌细胞系中MAP9蛋白呈高表达,而在EBV阴性胃癌细胞系则呈低表达[17]。本文研究以EBV阳性胃癌细胞系作为研究对象,探讨MAP9生物学作用,分析EBV对MAP9差异表达可能产生的影响,为阐明EBVaGC的发生发展提供实验依据。现将结果报告如下。

1 材料和方法 1.1 主要材料实验所用GT38为EBV阳性胃癌细胞系; 转染试剂LipofectamineTM2000购自美国Invitrogen公司; MAP9、β-actin单克隆抗体购自美国Abcam公司,CDK2、CDK6抗体购自美国CST公司; 凋亡检测试剂盒Annexin V-APC和PI均购自美国EBioscience公司; 细胞周期检测试剂盒购自美国Abcam公司; 细胞增殖-毒性检测试剂盒CCK-8购自Solarbio公司; 所用引物由上海吉玛公司合成,种类及其序列见表 1。

| 表 1 所用引物种类及其序列 |

|

|

GT38细胞以每孔5×104个接种于6孔板,于培养箱内培养,次日待细胞贴壁80%后即进行siRNA转染,8 h后更换含有血清的DMEM培养基继续培养,分别培养24、48、72 h,把转染阴性对照以及MAP9 siRNA的细胞分别设置为si-NC组、si-MAP9组。

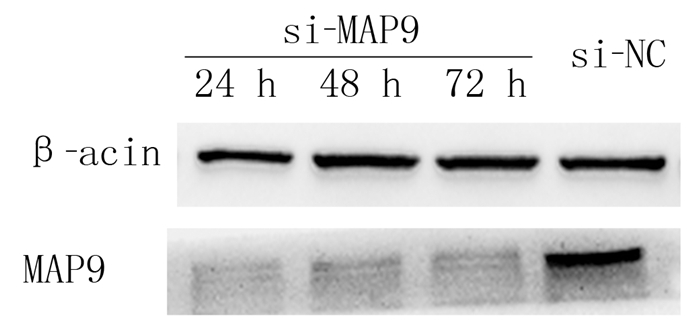

1.2.2 蛋白免疫印迹(Western blot)方法测定干扰效果取转染之后的细胞分别用PBS洗涤2次,再加入含有PMSF的RIPA裂解溶液,于冰上孵育30 min。以BCA法测定蛋白样品的浓度,每孔加入30 μg蛋白样品,85 V、120 min电泳,从玻璃板中间取出凝胶。将PVDF膜置于甲醇中孵育10 s后,300 mA、110 min转膜。加入50 g/L脱脂奶粉封闭60 min,加入一抗4 ℃孵育过夜。TBST洗10 min(共3次),加入适当比例稀释后的二抗,室温孵育60 min,TBST洗10 min(共3次),暗室内曝光。采用Image J分析内参β-actin和目的条带MAP9的灰度值,以MAP9的灰度值/β-actin的灰度值表示MAP9蛋白水平。每组实验重复3次。

1.2.3 细胞增殖和细胞毒性实验(CCK-8)检测细胞增殖收集对数期生长的细胞,调整细胞悬液密度至1×107/L,铺96孔板,每孔加100 μL细胞悬液,分别在转染24、48、72、96 h每孔加10 μL的CCK-8溶液,继续37 ℃孵育1 h后,用酶标仪检测450 nm波长处的吸光度。每组实验重复3次,每次设3个复孔。

1.2.4 流式细胞术检测细胞周期细胞转染之后,PBS洗2次,弃PBS,细胞沉淀加入提前预冷的体积分数0.66乙醇轻轻混匀,4 ℃固定至少2 h,最长可储存4周。上机前准备:4 ℃取出固定好的细胞,加入300~400 μL的PBS重悬,吹散成单细胞悬液,加入5 μL的RNase,放置15 min后加入5 μL浓度为10 pmol/L的PI。暗盒中避光,4 ℃孵育20~30 min,流式细胞仪上机检测,用Flowjo软件进行数据处理,观察细胞各期的比例。实验重复3次。

1.2.5 流式细胞术检测细胞凋亡细胞转染之后,PBS轻洗细胞2次,加入300 μL Binding Buffer重悬细胞,尽量吹打均匀呈单细胞悬液。采用Anne- xin V-APC和PI双染,取100 μL细胞悬液置于新的EP管中,依次加入5 μL APC和5 μL PI轻轻混匀。避光孵育15~30 min,1 h内通过流式细胞仪,上机检测两组细胞的凋亡情况。实验重复3次。1.2.6 Western blot检测细胞中相关蛋白表达变化按照1.2.2部分的Western blot方法,分别检测各组不同培养时间细胞CDK6、CDK2蛋白表达的变化,每组实验重复3次。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 17.0软件进行统计分析,计量资料结果以x±s形式表示,数据间比较采用Student’s t检验或方差分析(ANOVA)。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 siRNA干扰后GT38细胞中MAP9蛋白表达Western blot检测显示,应用GT38细胞转染MAP9基因siRNA后24、48和72 h,MAP9蛋白的表达水平分别为0.41±0.03、0.62±0.03、0.70±0.04,与si-NC组(2.25±0.04)比较均明显下降,差异有显著性(F=1 039.00,P < 0.001)。表明该序列可有效沉默MAP9的表达。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 Western blot检测siRNA干扰后GT38细胞中MAP9蛋白的表达 |

CCK-8检测结果显示,干扰MAP9表达后,细胞增殖数量升高,72、96 h时si-MAP9组吸光度值高于si-NC组,差异有显著意义(F=6.686、7.857,P < 0.001)。见表 2。

| 表 2 干扰MAP9后GT38细胞增殖情况(n=72, x±s) |

|

|

流式细胞仪检测结果显示,si-MAP9组处于S期细胞比例高于si-NC组,差异有统计学意义(t=2.880,P < 0.05)。见表 3。表明干扰MAP9表达可促进GT38细胞周期从G1期向S期转变。

| 表 3 细胞周期及凋亡率统计结果(n=6, χ/%, x±s) |

|

|

AnnexinV-FITC和PI试剂双染检测结果显示,si-MAP9组细胞凋亡率明显低于si-NC组,两组比较差异有统计学意义(t=4.699, P < 0.05)。见表 3。干扰MAP9表达后EBV阳性胃癌GT38细胞凋亡率明显降低。

2.5 干扰MAP9表达对EBV阳性胃癌GT38细胞CDK6、CDK2周期蛋白表达影响Western blot检测结果显示,干扰MAP9表达后,EBV阳性胃癌GT38细胞中周期蛋白CDK6和CDK2表达水平升高,与si-NC组相比较,差异有统计学意义(F=79.350、102.800,P < 0.001)。下调MAP9能促进CDK6、CDK2蛋白表达,从而促进细胞增殖。见图 2、表 4。

|

| 图 2 干扰MAP9后GT38细胞周期蛋白CKD6和CKD2表达Western blot检测 |

| 表 4 干扰MAP9后GT38细胞周期蛋白表达比较(n=12, x±s) |

|

|

诱导宿主细胞发生基因组不稳定是EBV促进肿瘤发生的关键因素。研究发现,EBV潜伏感染可通过引起宿主细胞DNA损伤、影响DNA损伤修复及干扰正常的细胞周期调控,进而诱发宿主细胞基因组不稳定[18-19]。在细胞有丝分裂过程中,双极纺锤体的形成是保证遗传物质在子代细胞间平均分配的必要条件; 单极或多极纺锤体的形成会导致染色体的异常分离,形成非整倍体,其被认为是肿瘤的特征之一。细胞有丝分裂是个连续变化的过程,任何基因的异常都可能导致有丝分裂的失败或错误,造成染色体缺失或重复,影响细胞分裂和DNA修复相关基因的表达,从而促进肿瘤的形成[20]。SHUMILOV等[21]的研究结果显示,EBV感染分裂中的细胞会导致细胞形成过多的纺锤体极,使染色体不再被准确而平均地分配到两个子代细胞中,导致染色体异常,促进了肿瘤的发生,说明EBV参与了肿瘤形成的早期过程。EBV诱发的胃癌是严重威胁人类健康的恶性肿瘤,EBVaGC预后差,复发、转移率高,目前临床上整体治疗效果仍不理想,寻找早期诊断的分子标志、治疗靶标及预后监测因子,对胃癌的治疗有重要作用[22]。

MAP9作为细胞周期的微管蛋白,调控细胞有丝分裂处于稳定的动态平衡,MAP9表达异常可导致遗传不稳定性,进而参与恶性肿瘤的形成[23]。然而,目前对MAP9与肿瘤关系的研究尚处于初期阶段[24-25]。VENOUX等[26]的研究结果表明,在骨肉瘤U-2OS、乳癌Cal51PE和Burkitt淋巴瘤Daudi等细胞系中均检测到了MAP9表达,而在结直肠癌LS174、早幼粒白血病NB4和淋巴瘤细胞系U937等细胞系中未检测到MAP9表达。ROUQUIER等[27]对结直肠癌组织和癌旁组织的检测结果显示,MAP9在癌组织中低表达。目前研究尚未能明确MAP9在肿瘤发生发展中的作用,而且MAP9转录表达的调控机制也无相关报道[28]。MAP9在肿瘤组织中表达及其作用可能与肿瘤组织和细胞类型有关,而EBVaGC是胃癌中的一种独特亚群[29]。我们的前期研究结果显示,MAP9蛋白在EBV阳性胃癌细胞系中呈高表达,而MAP9 mRNA和蛋白在EBV阴性胃癌细胞系中低表达或不表达,提示EBV促进MAP9表达可能是EBV参与胃癌发生的一种机制[17]。

一些研究表明,MAP9在DNA损伤的早期发挥作用,在受损细胞中MAP9与P53结合,可诱导P53蛋白的乙酰化和积累,抑制MDM2介导的P53降解。MAP9在EBV阳性细胞系中的异常高表达是一种失衡和紊乱,因此,作为DNA损伤的受体成分,MAP9的突变和失衡可能通过P53信号通路参与肿瘤的发生和发展,进而调控EBVaGC细胞的增殖和凋亡[30]。

细胞周期素依赖性激酶(CDK)是一组与细胞周期过程相对应的Ser/thr激酶, 所有类型的CDK在细胞周期中交替激活,磷酸化相应的底物,使细胞周期过程有条不紊地继续下去[31]。CDK6和CDK2在细胞周期进程中起着重要的作用,是调控细胞周期进程中G1期限制点的关键分子,相关研究结果表明,CDK6和CDK2蛋白的表达对正常细胞周期进程至关重要[32]。

本文研究结果显示,应用siRNA干扰EBV阳性胃癌细胞系GT38中MAP9基因的表达后,细胞S期比例上升,增殖能力增强,CDK6、CDK2周期蛋白表达上调,细胞凋亡率降低,提示MAP9可能通过调控CDK相关周期激酶而抑制EBV阳性胃癌细胞系GT38的增殖,并且MAP9能促进GT38细胞的凋亡。说明MAP9可能通过调控CDK相关周期激酶而抑制EBV阳性胃癌细胞系GT38的增殖。本文细胞凋亡实验结果显示,MAP9能促进GT38细胞的凋亡。该结果提示MAP9可能是胃癌发生发展中一个重要的抑癌因素,在EBVaGC的发生发展中起到抑癌基因的作用。

| [1] |

ALI A S, AL-SHRAIM M, AL-HAKAMI A M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus: clinical and epidemiological revisits and genetic basis of oncogenesis[J]. The Open Virology Journal, 2015, 9: 7-28. DOI:10.2174/1874357901509010007 |

| [2] |

WU R, SATTARZADEH A, RUTGERS B, et al. The microenvironment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma: heterogeneity by Epstein-Barr virus presence and location within the tumor[J]. Blood Cancer Journal, 2016, 6(1): e417. |

| [3] |

ROSALES-PÉREZ S, CANO-VALDEZ A M, FLORES-BALCÁZAR C H, et al. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein (LMP-1), p16 and p53 proteins in nonendemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC): a clinicopathological study[J]. Archives of Medical Research, 2014, 45(3): 229-236. DOI:10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.02.002 |

| [4] |

HUANG S C, NG K F, CHEN K F, et al. Prognostic factors in Epstein-Barr virus-associated stage Ⅰ-Ⅲ gastric carcinoma: implications for a unique type of carcinogenesis[J]. Oncology Reports, 2014, 32(2): 530-538. DOI:10.3892/or.2014.3234 |

| [5] |

CAMARGO M C, KIM W H, CHIARAVALLI A M, et al. Improved survival of gastric Cancer with tumour Epstein-Barr virus positivity: an international pooled analysis[J]. Gut, 2014, 63(2): 236-243. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304531 |

| [6] |

WU J, SU H, LI G, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) regulates the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) positive cell population in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines[J]. Acta Virologica, 2019, 63(3): 322-327. DOI:10.4149/av_2019_308 |

| [7] |

DAVOLI T, XU A W, MENGWASSER K E, et al. Cumulative haploinsufficiency and triplosensitivity drive aneuploidy patterns and shape the cancer genome[J]. Cell, 2013, 155(4): 948-962. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.011 |

| [8] |

WANG Fang, WU Jingyi, WANG Yan, et al. Gut microbiota functional biomolecules with Immune-Lipid metabolism for a prognostic compound score in Epstein-Barr Virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma: a pilot study[J]. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 2019, 10(10): e00074. DOI:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000074 |

| [9] |

GE Yanshan, LONG Yuehua, XIAO Songshu, et al. CD38 affects the biological behavior and energy metabolism of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells[J]. International Journal of Oncology, 2019, 54(2): 585-599. |

| [10] |

FERLAY J, SOERJOMATARAM I, DIKSHIT R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. International Journal of Cancer (Journal International du Cancer), 2015, 136(5): e359-e386. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29210 |

| [11] |

SOURISSEAU M, LAWRENCE D J, SCHWARZ M C, et al. Deep mutational scanning comprehensively maps how Zika envelope protein mutations affect viral growth and antibody escape[J]. Journal of Virology, 2019, 93(23): e01291. |

| [12] |

RAMKUMAR A, JONG B Y, ORI-MCKENNEY K M. ReMAPping the microtubule landscape: how phosphorylation dictates the activities of microtubule-associated proteins[J]. Developmental Dynamics, 2018, 247(1, SI): 138-155. |

| [13] |

FONTENILLE L, ROUQUIER S, LUTFALLA G, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 9 (Map9/Asap) is required for the early steps of zebrafish development[J]. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.), 2014, 13(7): 1101-1114. DOI:10.4161/cc.27944 |

| [14] |

YANG Jian, YU Yang, LIU Wei, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau is associated with the resistance to docetaxel in prostate cancer cell lines[J]. Research and Reports in Urology, 2017, 9: 71-77. DOI:10.2147/RRU.S118966 |

| [15] |

VENOUX M, DELMOULY K, MILHAVET O, et al. Gene organization, evolution and expression of the microtubule-associated protein ASAP (MAP9)[J]. BMC Genomics, 2008, 9: 406. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-9-406 |

| [16] |

FORMAN O P, HITTI R J, BOURSNELL M, et al. Canine genome assembly correction facilitates identification of a MAP9 deletion as a potential age of onset modifier for RPGRIP1-associated canine retinal degeneration[J]. Mammalian Genome, 2016, 27(5/6): 237-245. |

| [17] |

肖华. EBV相关胃癌中EBV对MAP9表达影响的研究[D].青岛: 青岛大学, 2018.

|

| [18] |

KOHLI R M, ZHANG Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation[J]. Nature, 2013, 502(7472): 472-479. DOI:10.1038/nature12750 |

| [19] |

NAMBA-FUKUYO H, FUNATA S, MATSUSAKA K, et al. TET2 functions as a resistance factor against DNA methylation acquisition during Epstein-Barr virus infection[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(49): 81512-81526. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.13130 |

| [20] |

GRUHNE B, SOMPALLAE R, MASUCCI M G. Three Epstein-Barr virus latency proteins independently promote genomic instability by inducing DNA damage, inhibiting DNA repair and inactivating cell cycle checkpoints[J]. Oncogene, 2009, 28(45): 3997-4008. DOI:10.1038/onc.2009.258 |

| [21] |

SHUMILOV A, TSAI M H, SCHLOSSER Y T, et al. Epstein-Barr virus particles induce centrosome amplification and chromosomal instability[J]. Nat Commun, 2017, 8: 14257. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14257 |

| [22] |

FUKUDA M, LONGNECKER R. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A mediates transformation through constitutive activation of the Ras/PI3-K/Akt pathway[J]. Journal of Virology, 2007, 81(17): 9299-9306. DOI:10.1128/JVI.00537-07 |

| [23] |

SAFFIN J M, VENOUX M, PRIGENT C, et al. ASAP, a human microtubule-associated protein required for bipolar spindle assembly and cytokinesis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(32): 11302-11307. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0500964102 |

| [24] |

KONG Yao, NIE Zhikui, LI Feng, et al. MiR-320a was highly expressed in postmenopausal osteoporosis and acts as a negative regulator in MC3T3E1 cells by reducing MAP9 and inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway[J]. Experimental and Molecular Pathology, 2019, 110: 104282. DOI:10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.104282 |

| [25] |

ZHENG Yansong, ZHENG Yongtian, LEI Wendi, et al. miR-1307-3p overexpression inhibits cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis by targeting ISM1 in colon cancer[J]. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 2019, 48: 101445. DOI:10.1016/j.mcp.2019.101445 |

| [26] |

VENOUX M, BASBOUS J, BERTHENET C, et al. ASAP is a novel substrate of the oncogenic mitotic kinase Aurora-A: phosphorylation on Ser625 is essential to spindle formation and mitosis[J]. Human Molecular Genetics, 2008, 17(2): 215-224. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddm298 |

| [27] |

ROUQUIER S, PILLAIRE M J, CAZAUX C A. Expression of the microtubule-associated protein MAP9/ASAP and its partners AURKA and PLK1 in colorectal and breast cancers[J]. Disease Markers, 2014, 2014: 798170. |

| [28] |

EOT-HOULLIER G, VENOUX M, VIDAL-EYCHENIE S A, et al. Plk1 regulates both ASAP localization and its role in spindle Pole integrity[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2010, 285(38): 29556-29568. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.144220 |

| [29] |

WANG J Y, NAGY N, MASUCCI M G. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1 upregulates the cellular antioxidant defense to enable B-cell growth transformation and immortalization[J]. Oncogene, 2020, 39(3): 603-616. DOI:10.1038/s41388-019-1003-3 |

| [30] |

BASBOUS J, KNANI D, BONNEAUD N, et al. Induction of ASAP (MAP9) contributes to p53 stabilization in response to DNA damage[J]. Cell Cycle, 2012, 11(12): 2380-2390. DOI:10.4161/cc.20858 |

| [31] |

CHIBAZAKURA T, ASANO Y. Defective interaction between p27 and cyclin A-CDK complex in certain human cancer cell lines revealed by split YFP assay in living cells[J]. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 2017, 81(12): 2360-2366. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2017.1391686 |

| [32] |

CHENG Weiyan, YANG Zhiheng, WANG Suhua, et al. Recent development of CDK inhibitors: an overview of CDK/inhibitor co-crystal structures[J]. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2019, 164: 615-639. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.003 |

2020, Vol. 56

2020, Vol. 56