肺癌是我国发病率和死亡率均较高的一种恶性肿瘤, 其中非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)占肺癌病人的80%~85%[1]。多数病人早期无明显症状及体征, 就诊时多处于中晚期, 治疗困难, 预后较差。早期肺癌治疗以手术切除为主, 中晚期肺癌手术切除配合放化疗、靶向治疗及免疫治疗等综合措施[2-3]。肺癌发生发展涉及多种细胞因子、多条信号通路, 其发病机制一直是研究热点。晚期糖基化终末产物受体(RAGE)是一种跨膜的信号转导受体, 属于免疫球蛋白超家族, 与相关配体结合后, 会激活胞内多种信号转导通路, 引起相应的生物学效应[4-5]。RAGE在恶性肿瘤如肝癌、胃癌、胰腺癌及前列腺癌等的表达异常增加, 与癌细胞的增殖、迁移、侵袭及肿瘤的分期和预后等密切相关[6-10]。S100蛋白(S100P)属于钙结合蛋白家族, 可以与RAGE结合介导肿瘤如黑色素瘤的发生[11-12]。信号转导和转录激活因子3(STAT3)为常见癌基因之一, 其异常激活与肿瘤的生物学效应密切相关[13-14]。Pim-1是一种癌基因, 有研究表明Pim-1是细胞因子信号通路传导的下游效应因子, 能够通过改变细胞周期调节因子的活性而缩短细胞周期, 参与调控细胞的增殖、分化和凋亡[15]。本文研究采用Western blot和RT-PCR方法, 分别检测NSCLC病人癌组织及其癌旁组织中RAGE、S100P、STAT3和Pim1蛋白和基因表达, 分析其在病人不同临床病理特征下的差异性表达, 旨在探讨以上因子在NSCLC中的表达和意义。

1 材料与方法 1.1 标本及其来源标本来自2018年4—8月青岛大学附属医院胸外科手术切除且病理证实为NSCLC的病人(均由两位病理医师独立诊断), 共40例, 男24例, 女16例; 年龄43~81岁, 中位年龄61岁。病人临床资料完整, 术前均未行其他抗肿瘤治疗。标本为每例病人的肺癌组织及对应的癌旁正常肺组织(距癌灶边缘5 cm)。研究经青岛大学附属医院伦理委员会批准, 并获得病人知情同意书。

1.2 RAGE、S100P、STAT3等蛋白表达检测采用Western blot方法进行检测。取冻存肺组织, 每250 mg组织加入1 mL RIPA裂解液, 使用匀浆器于冰上研磨组织静置30 min; 4 ℃、12 000 r/min离心10 min, 取上清液; 行SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳, 湿转法转移至PVDF膜上, 然后用50 g/L脱脂奶粉封闭2 h, 分别加入含对应一抗Anti-RAGE、Anti-S100P、Anti-STAT3、Anti-Pim1(赛尔生物, 天津)的Blotto, 4 ℃摇床孵育过夜; 再加入HRP标记山羊抗兔IgG二抗(abcam, USA)Blotto于37 ℃室温下静置孵育1.5 h, 将膜置于TBST溶液中摇动漂洗5 min, 共4次; Western LightningTM Chemiluminescence Reagent显色剂(PerkinElmer, 美国)中显色30 s。最后用LabWorksTM凝胶成像及分析系统(UVP, 美国)进行摄像, 计算各组蛋白条带的灰度值, 以其表示各蛋白表达。

1.3 RAGE、S100P、STAT3及Pim1 mRNA表达检测采用RT-PCR方法。充分研磨冻存NSCLC组织及癌旁正常肺组织, 加入适量裂解液, 离心, 取上清液, 应用Trizol法提取组织总RNA; 将3 μL总RNA加入到13.5 μL反应体系中进行反转录, 得到cDNA。荧光定量PCR(Takara, Japan)方法扩增RAGE、S100P、STAT3、Pim1及β-actin、U6sn-RNA基因。循环参数为:94 ℃、4 min; 94 ℃、30 s, 56 ℃、30 s, 72 ℃、30 s; 共40个循环。各样品目的基因和管家基因分别进行荧光定量PCR反应。目的基因扩增产物的相对含量用2-△△Ct表示。各基因引物序列见表 1。

| 表 1 RT-PCR引物碱基序列 |

|

|

应用SPSS 19.0软件进行统计学分析, 计量资料结果用x±s形式表示, 数据间比较采用t检验; 相关性分析采用Pearson相关检验法。P < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

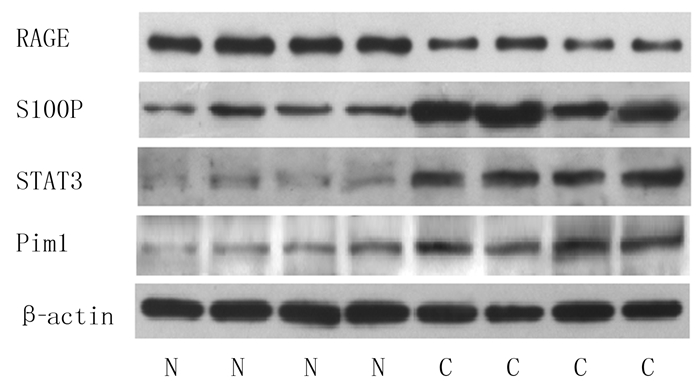

2 结果 2.1 两种组织中RAGE、S100P、STAT3及Pim1蛋白表达比较与癌旁正常组织相比, 肺癌组织中RAGE蛋白表达明显减少(t=5.756, P < 0.05), S100P、STAT3、Pim1蛋白表达明显增高, 差异均有统计学意义(t=2.414 ~10.141, P < 0.05)。见图 1、表 2。

|

| N:癌旁组织, C:肺癌组织。 图 1 两种组织RAGE、S100P、STAT3、Pim1蛋白表达的Western blot检测 |

| 表 2 两种组织中RAGE、S100P、STAT3、Pim1蛋白表达比较(n=12, x±s) |

|

|

与癌旁正常组织相比较, 肺癌组织中的RAGE mRNA表达明显减少, S100P、STAT3以及Pim1 mRNA表达明显增多, 差异有显著性(t=10.430~21.530, P < 0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 两种组织RAGE、S100P、STAT3和Pim1 mRNA相对表达量比较(n=40, x±s) |

|

|

RAGE和S100P mRNA表达与肺癌病人的性别、年龄、癌组织大小均无关(P>0.05);腺癌组织RAGE mRNA表达明显高于鳞癌组织, 高中分化组织表达高于低分化组织, 伴有淋巴结转移肺癌组织中的表达明显低于不伴有淋巴结转移肺癌组织, 差异均有统计学意义(t=2.157~2.908, P < 0.05);S100P mRNA在鳞癌组织中的表达明显高于腺癌组织, 在低分化组织中的表达明显高于高中分化组织, 在伴有淋巴结转移的癌组织中的表达明显高于不伴有淋巴结转移的癌组织, 差异有统计学意义(t=2.132~2.590, P < 0.05)。见表 4。

| 表 4 RAGE、S100P mRNA表达与NSCLC病人临床病理参数的关系(x±s) |

|

|

NSCLC组织中RAGE的表达与S100P表达、STAT3表达呈负相关(r=-0.430、-0.417, P < 0.05), STAT3表达与S100P表达、S100P表达与Pim1表达、Pim1表达与miR-21表达均呈正相关(r=0.324~0.337, P < 0.05)。

3 讨论RAGE作为一种模式识别受体, 可以与多种配体结合介导疾病的发生发展。RAGE在肺泡上皮细胞中呈高表达, 维持肺泡的正常形态结构及稳定性, 介导肺泡上皮细胞与基底膜的黏附; RAGE减少可导致去极化和去分化, 细胞功能破坏, 与肿瘤细胞的增殖、侵袭和迁移有关[16]。已有研究结果发现, RAGE在胃癌、胰腺癌、乳癌等中高表达[6, 8-9], 但在肺癌组织中低表达, 被认为发挥抑癌基因的作用[5]。目前, 对于RAGE-配体结合在肿瘤中的调控机制的研究越来越多, 其主要的配体S100家族在其中发挥着重要的作用[17]。S100P与RAGE结合后可以导致ERK1/2发生磷酸化, 激活MAPK/ERK信号途径[18]。有研究表明, S100P在结肠癌、胰腺癌等高表达[19-21], S100P可能通过与整合素α7相互作用活化激酶FAK和AKT而促进肺癌细胞的转移和侵袭[22]。在体实验和细胞实验发现, Keap1-Nrf2轴可以通过靶向S100P而抑制肺腺癌的迁移和进展[23]; AGER/RAGE介导的自噬可能通过IL-6/STAT3信号途径促进胰腺癌的发生[24]。本文研究结果表明, 肺癌组织RAGE蛋白表达低于正常组织, S100P、STAT3和Pim1蛋白表达明显高于正常组织。此外, 我们还发现与癌旁组织相比, 肺癌组织中RAGE mRNA表达明显减少, S100P、STAT3、Pim1 mRNA表达明显增多, 与其蛋白水平表达情况一致。说明肺癌病人RAGE表达减少, S100P、STAT3、Pim1表达增多。有研究发现RAGE在肺癌组织中表达较低[5], 基因芯片技术筛选出的差异性基因包括S100P等参与早期NSCLC[25], JAK/STAT3活化参与NSCLC的发生发展[26], Pim1在肺腺癌中过表达与肿瘤的侵袭、转移有关[27], 本文研究结果与以上文献报道基本一致。本文分析了不同临床病理参数NSCLC病人RAGE和S100P mRNA表达差异, 结果显示RAGE、S100P表达在不同年龄、性别、肿瘤大小病人间差异无统计学意义; RAGE在NSCLC腺癌中表达较高, S100P在鳞癌中表达较高, 提示两者可能与肺癌的病理形态特征有关; RAGE在高中分化NSCLC组织中表达较高, 在无淋巴结转移的NSCLC组织中表达较高; 而S100P在低分化NSCLC组织中表达较高, 在有淋巴结转移的肺癌组织中表达较高, 提示两者可能影响肿瘤的生物学行为, 其异常表达可能与肿瘤的增殖、侵袭和转移有关。RAGE在正常肺组织中高表达, 可发挥信号传导功能和黏附分子的作用, 维持正常细胞的增殖、代谢、死亡等; 在某些内外刺激的作用下被降解或表达下调, 从而导致其调控的下游分子异常表达介导肿瘤发生。结合对其他恶性肿瘤的研究, RAGE及其配体S100P在肿瘤发生发展中的作用机制复杂, 在NSCLC中两者可能存在不同于其他肿瘤中的负反馈调节机制或者拮抗作用, 其对肿瘤的作用可能具有双向性, 具体作用取决于组织细胞的类型、细胞所处的微环境和相应的上下游分子等, 有待进一步证实。

MELOCHE等[28]通过体外实验发现, STAT3可以依赖RAGE激活Pim1, 通过促进转录因子NFAT的表达而促进血管内皮细胞的增殖和抗凋亡; RAGE低表达可减少STAT/Pim1/NFAT的活化, 逆转大鼠损伤的冠脉血管重塑。BLOCK等[29]对胰腺癌细胞研究发现, IL-6可以激活STAT3, 上调Pim1的表达, 同时IL-6的表达也会因此升高, 从而对肿瘤的进展产生正反馈的作用。结肠癌组织中氧化应激反应产生的活性氧可抑制JAK2/STAT3通路, 从而抑制Pim1的表达。Pim1作为原癌基因其表达下调会抑制癌细胞生长, 促进癌细胞凋亡, 使其侵袭转移受限, 从而达到治疗的目的[30]。本文相关性分析显示, RAGE与S100P、STAT3可能存在拮抗作用, S100P、STAT3和Pim1存在协同作用。结合以上文献报道及本文研究结果, 推测RAGE、S100P、STAT3和Pim1及其他下游因子等信号通路可能参与NSCLC的发生发展, 有待于进一步研究证实。

NSCLC的发生发展是多因子、多因素共同作用的结果, 其确切机制目前还不明确。RAGE、S100P、STAT3和Pim1具有调控细胞增殖、侵袭、分化和凋亡等重要作用, 但是其在肺癌发生发展过程中的确切作用尚不清楚, 与临床疾病发展之间的关系尚需要进一步研究。

| [1] |

SIEGEL R L, MILLER K D, JEMAL A. Cancer statistics, 2019[J]. CA-A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2019, 69(1): 7-34. DOI:10.3322/caac.21551 |

| [2] |

HIRSCH F R, SCAGLIOTTI G V, MULSHINE J L, et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(166): 299-311. |

| [3] |

OSMANI L, ASKIN F, GABRIELSON E, et al. Current WHO guidelines and the critical role of immunohistochemical markers in the subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): moving from targeted therapy to immunotherapy[J]. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2018, 52(Pt 1): 103-109. |

| [4] |

AHMAD S, KHAN H, SIDDIQUI Z, et al. AGEs, RAGEs and s-RAGE; friend or foe for cancer[J]. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 2018, 49: 44-55. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.07.001 |

| [5] |

WU Shuangshuang, MAO Liping, LI Yan, et al. RAGE may act as a tumour suppressor to regulate lung cancer development[J]. Gene, 2018, 651: 86-93. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2018.02.009 |

| [6] |

KWAK T, DREWS-ELGER K, ERGONUL A, et al. Targeting of RAGE-ligand signaling impairs breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis[J]. Oncogene, 2017, 36(11): 1559-1572. DOI:10.1038/onc.2016.324 |

| [7] |

HOLLENBACH M. The role of Glyoxalase-I (Glo-I), advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), and their receptor (RAGE) in chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2017, 18(11): 2466. DOI:10.3390/ijms18112466 |

| [8] |

HU Dan, LIU Qing, LIN Xiandong, et al. Association of RAGE gene four single nucleotide polymorphisms with the risk, invasion, metastasis and overall survival of gastric cancer in Chinese[J]. Journal of Cancer, 2019, 10(2): 504-509. DOI:10.7150/jca.26583 |

| [9] |

AZIZAN N, SUTER M A, LIU Y, et al. RAGE maintains high levels of NFκB and oncogenic Kras activity in pancreatic cancer[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2017, 493(1): 592-597. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.147 |

| [10] |

KOLONIN M G, SERGEEVA A, STAQUICINI D I, et al. Interaction between tumor cell surface receptor RAGE and proteinase 3 mediates prostate cancer metastasis to bone[J]. Cancer Research, 2017, 77(12): 3144-3150. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0708 |

| [11] |

XIONG Tingfeng, PAN Fuqiang, LI Dong. Expression and clinical significance of S100 family genes in patients with melanoma[J]. Melanoma Research, 2019, 29(1): 23-29. DOI:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000512 |

| [12] |

ZHU L, ITO T, NAKAHARA T, et al. Upregulation of S100P, receptor for advanced glycation end products and ezrin in malignant melanoma[J]. The Journal of Dermatology, 2013, 40(12): 973-979. DOI:10.1111/1346-8138.12323 |

| [13] |

CHAI E Z, SHANMUGAM M K, ARFUSO F, et al. Targeting transcription factor STAT3 for cancer prevention and therapy[J]. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2016, 162: 86-97. |

| [14] |

YANG Mengqi, CHEN Huanting, ZHOU Lin, et al. Expression profile and prognostic values of STAT family members in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. American Journal of Translational Research, 2019, 11(8): 4866-4880. |

| [15] |

ZHU Qiaojuan, LI Yazhao, GUO Yang, et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG16 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by targeting miR-497-5p/PIM1 axis[J]. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2019, 23(11): 7395-7405. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.14601 |

| [16] |

SIMS G P, ROWE D C, RIETDIJK S T, et al. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer[J]. Annual Review of Immunology, 2010, 28: 367-388. DOI:10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132603 |

| [17] |

LIU Qiongqiong, HUO Yansong, ZHENG Hong, et al. Ethyl pyruvate suppresses the growth, invasion and migration and induces the apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells via the HMGB1/RAGE axis and the NF-κB/STAT3 pathway[J]. Oncology Reports, 2019, 42(2): 817-825. |

| [18] |

TESAROVA P, KALOUSOVA M, ZIMA T, et al. HMGB1, S100 proteins and other RAGE ligands in cancer-markers, mediators and putative therapeutic targets[J]. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, 2016, 160(1): 1-10. DOI:10.5507/bp.2016.003 |

| [19] |

MERCADO-PIMENTEL M E, ONYEAGUCHA B C, LI Q, et al. The S100P/RAGE signaling pathway regulates expression of microRNA-21 in colon cancer cells[J]. FEBS Letters, 2015, 589(18): 2388-2393. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.010 |

| [20] |

NAKAYAMA H, OHUCHIDA K, YONENAGA A, et al. S100P regulates the collective invasion of pancreatic cancer cells into the lymphatic endothelial monolayer[J]. International Journal of Oncology, 2019, 55(1): 211-222. |

| [21] |

NAKAYAMA H, OHUCHIDA K, YONENAGA A, et al. S100P regulates the collective invasion of pancreatic cancer cells into the lymphatic endothelial monolayer[J]. International Journal of Oncology, 2019, 55(1): 211-222. |

| [22] |

HSU Y L, HUNG J Y, LIANG Y Y, et al. S100P interacts with integrin α7 and increases cancer cell migration and invasion in lung cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(30): 29585-29598. |

| [23] |

CHIEN M H, LEE W J, HSIEH F K, et al. Keap1-Nrf2 interaction suppresses cell motility in lung adenocarcinomas by targeting the S100P protein[J]. Clinical Cancer Research: an Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 2015, 21(20): 4719-4732. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2880 |

| [24] |

KANG R, TANG D L, LOTZE M T, et al. AGER/RAGE-mediated autophagy promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis and bioenergetics through the IL6-pSTAT3 pathway[J]. Autophagy, 2012, 8(6): 989-991. DOI:10.4161/auto.20258 |

| [25] |

TIAN Wen, LIU Jie, PEI Baojing, et al. Identification of miRNAs and differentially expressed genes in early phase non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Oncology Reports, 2016, 35(4): 2171-2176. DOI:10.3892/or.2016.4561 |

| [26] |

ZHENG Xianan, LU Guohua, YAO Yinan, et al. An autocrine IL-6/IGF-1R loop mediates EMT and promotes tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 2019, 15(9): 1882-1891. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.31999 |

| [27] |

CAO Lianjing, WANG Fan, LI Shouying, et al. PIM1 kinase promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and tumor growth of lung adenocarcinoma by potentiating the c-MET signaling pathway[J]. Cancer Letters, 2019, 444: 116-126. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2018.12.015 |

| [28] |

MELOCHE J, PAULIN R, COURBOULIN A, et al. RAGE-dependent activation of the oncoprotein Pim1 plays a critical role in systemic vascular remodeling processes[J]. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, 2011, 31(9): 2114-2124. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.230573 |

| [29] |

BLOCK K M, HANKE N T, MAINE E A, et al. IL-6 stimulates STAT3 and Pim-1 kinase in pancreatic cancer cell lines[J]. Pancreas, 2012, 41(5): 773-781. |

| [30] |

LIU Kaili, GAO Hui, WANG Qiaoyun, et al. Hispidulin suppresses cell growth and metastasis by targeting PIM1 through JAK2/STAT3 signaling in colorectal cancer[J]. Cancer Science, 2018, 109(5): 1369-1381. DOI:10.1111/cas.13575 |

2020, Vol. 56

2020, Vol. 56