骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤均是常见的骶尾部肿瘤。而且这两种肿瘤具有许多相似的特征, 如好发于成年人、通常在脊柱的前部出现、生长缓慢、跨椎体生长等[1-7]。目前, 国内很少有研究对骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤单独进行影像学鉴别诊断。为了提高对这两种肿瘤诊断的准确率, 本研究回顾性分析经手术病理证实的骶尾部骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤的影像学表现。现将结果报告如下。

1 资料和方法 1.1 一般资料2010年6月—2017年6月, 收集青岛大学附属医院经手术病理证实的骶尾部骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤病人的影像学资料。骨巨细胞瘤病人11例, 男4例, 女7例; 年龄22~51岁, 中位年龄34岁; 8例因腰背部不适就诊, 3例因其他原因就诊; 术前10例接受CT平扫检查, 9例接受MRI检查。脊索瘤病人18例, 男10例, 女8例; 年龄37~76岁, 中位年龄59岁; 15例因腰骶部隐痛就诊, 3例因下肢不适就诊; 术前15例接受CT平扫检查, 13例接受MRI检查。本研究获我院伦理委员会批准, 研究对象均签署知情同意书。

1.2 影像学检查 1.2.1 CT检查采用GE Light Speed 16、GE Bright Speed 16和Siemens Sensation Cardiac 64层MSCT机检查。先进行常规轴位平扫, 管电流250 mA, 管电压120 kV, 层厚5 mm, 层间距2 mm, 选取骨窗和软组织窗观察, 再进行冠状位和矢状位重建。

1.2.2 MRI检查采用GE 3.0 T磁共振成像系统及脊柱专用线圈进行MRI扫描, 矩阵256×256。扫描序列及其参数如下。矢状位:FSE T1WI(TR 820、TE 9.369、NEX 4、FOV 40 cm、层厚5 mm、层间距1 mm), FSE T2WI(TR 2 940、TE 85.816、NEX 4、FOV 40 cm、层厚5 mm、层间距1 mm), STIR(TR 3 800、TE 38.920、NEX 4、FOV 40 cm、层厚5 mm、层间距1 mm); 冠状位:STIR(TR3 600、TE 36.256、NEX 4、FOV 40 cm、层厚5 mm、层间距1 mm); 横轴位:STIR (TR 3 200、TE 34.352、NEX 4、FOV 20 cm、层厚5 mm、层间距1 mm)。

1.3 图像分析由两位放射科高年资肌骨专业医师在PACS系统中对影像进行评价, 分别对病人的性别、年龄、发病部位、肿瘤生长方式、病变累及部位、有无椎旁软组织包块、是否累及椎间隙、T2压脂信号特点、是否有骨性结构、有无囊性改变、肿瘤内部有无钙化或残留骨、是否有不完整骨壳等12项指标进行统计和分析。两位医师意见不同时, 经协商取得一致意见。

1.4 统计学分析采用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析, 计数资料的比较采用四格表卡方检验, 检验水准α=0.05。

2 结果 2.1 CT表现行CT检查的10例骨巨细胞瘤中7例有钙化或残留骨, 15例脊索瘤中12例有钙化或残留骨, 两者之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);行CT检查的10例骨巨细胞瘤中1例骨性包壳不完整, 15例脊索瘤骨性包壳全都不完整, 两者之间差异有统计学意义(χ2=21.094, P < 0.05)。

2.2 MRI表现骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤T2压脂像均呈不均匀高信号, 两者之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。行MRI检查的9例骨巨细胞瘤中6例有低信号骨性间隔, 13例脊索瘤中9例有低信号骨性间隔, 两者之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);9例骨巨细胞瘤中6例有囊性改变, 13例脊索瘤中4例有囊性改变, 两者之间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

2.3 两种肿瘤影像学表现比较骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤相比较, 发病年龄、发病部位、肿瘤生长方式、椎旁有无软组织包块、病变累及部位、病变是否累及椎间隙等指标比较, 差异均有统计学意义(χ2=5.578~24.976, P < 0.05), 而病人性别差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 1。典型征象及典型病例分别见图 1、2。

| 表 1 两种肿瘤影像学表现比较(例) |

|

|

|

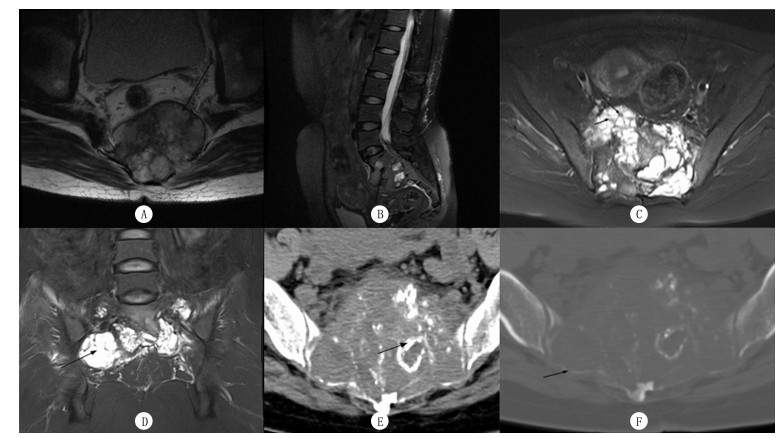

| A~D为MRI检查, E、F为CT检查。A箭头示椎旁软组织包块; B箭头示病变累及椎间隙; C箭头示短T2信号的骨性间隔; D箭头示囊性改变; E箭头示钙化或残留骨; F箭头示骨壳不完整。 图 1 两种肿瘤CT和MRI检查的典型征象 |

|

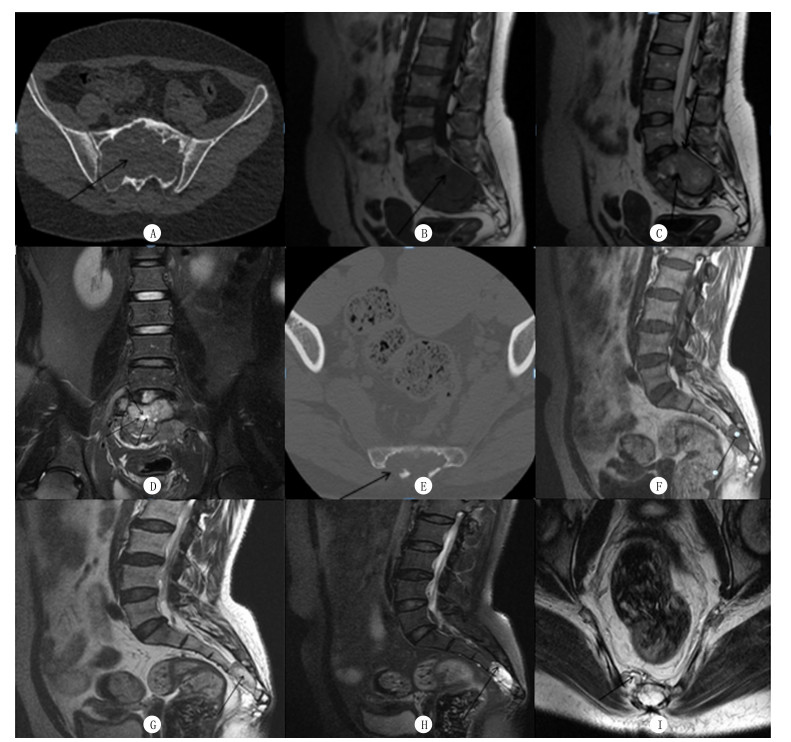

| A~D:骨巨细胞瘤病人, 女, 34岁, 因腰背部不适就诊。CT平扫检查:S1~S3椎体呈膨胀性骨质破坏, 骨壳相对完整, 包块内密度欠均匀, 其内见散在碎骨片(A); MRI平扫检查:包块呈长T1、稍短T2信号影, 其内信号不均(B、C), 见斑片状长T2信号影(C), 周围环绕短T2信号线样信号影(D), 包块局部向后突入椎管(C)。E~I:脊索瘤病人, 女, 52岁, 因腰骶部隐痛就诊。CT平扫检查:S4~S5椎体呈溶骨性骨质破坏, 骨壳不完整, 其内密度不均(E); MRI平扫检查:包块呈长T1、长T2信号影(F、G), T2压脂像呈高信号(H), S4~S5椎间隙受累, 病变在椎旁形成软组织包块(I), 包块局部向后突入椎管。 图 2 两种肿瘤典型病例的CT和MRI表现 |

骨巨细胞瘤是具有局部侵袭性的良性肿瘤, 其治疗目标是手术尽可能彻底切除肿瘤。然而, 手术切除后肿瘤复发率很高, 在某些情况下, 手术彻底切除肿瘤是不可能的。近年来, 在新辅助治疗方面的一些进展为骨巨细胞瘤的治疗带来一些新的策略, 如立体定向放射治疗、选择性动脉栓塞术、狄诺塞麦治疗法等[8]。脊索瘤是罕见的低到中度恶性骨肿瘤, 它起源于胚胎时期残余的脊索组织。整体切除包块及周围广泛的边缘是治疗的关键, 因为这与脊索瘤复发的高风险和长期生存率的降低有关[9]。近年来的研究结果显示, 碳离子和质子束放射治疗可以使肿瘤及其并发症得到有效控制[10-11]。

骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤均需由病理确诊, 但在活检之前可通过影像学检查缩小诊断范围。区分骶尾部骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤的一个重要特征是病人的年龄, 有文献报道骨巨细胞瘤好发年龄为20~40岁, 脊索瘤好发年龄为40~60岁[12-14]。本研究中, 骨巨细胞瘤病人的发病年龄低于脊索瘤病人, 差异有统计学意义, 与文献报道相符。因此, 年龄是两者鉴别诊断的重要参数。骶尾部是脊索瘤和骨巨细胞瘤发病的常见部位, 最常见的骶尾部好发肿瘤是脊索瘤, 其次是骨巨细胞瘤。本研究中, 骨巨细胞瘤大都位于S3以上部位, 而脊索瘤全位于S3以下, 两者比较差异有统计学意义, 与SI等[15]报道的结果相一致。脊索瘤的这种发病部位分布与脊索组织的发生学密切相关。此外, 肿瘤的生长方式(膨胀性/溶骨性)及椎旁有无软组织包块也是鉴别这两种肿瘤的重要参数。本研究中, 骨巨细胞瘤大都呈膨胀性生长, 极少数有溶骨性骨质破坏, 而脊索瘤全部有溶骨性骨质破坏, 这可能与两者发病的部位和恶性程度不同有关。骨巨细胞瘤少数在椎管外形成软组织包块, 而脊索瘤易在椎管外形成软组织包块。这与肿瘤的恶性程度有关, 脊索瘤的侵袭程度较骨巨细胞瘤高, 容易造成骨质破坏, 肿瘤易突破骨壳向外生长, 故易在椎管外形成软组织包块。骨巨细胞瘤以累及单椎体多见, 椎间隙易受累, 而脊索瘤更为多见的是累及多椎体且椎间隙不易受累, 这很可能与肿瘤的生长方式有关。在CT表现中, 观察骨壳的完整性对骨巨细胞瘤来说是重要的, 因为骨巨细胞瘤偏良性, 并且生长缓慢, 故骨壳多完整。相比之下, 完整的骨壳在脊索瘤中并不常见, 因为脊索瘤属于恶性骨肿瘤, 容易破坏骨皮质生长到椎管外。当脊索瘤发生在S3以下, 椎管外肿瘤容易变大, 因为肿瘤在盆腔内生长没有症状。MRI平扫表现中, 两者没有明显可鉴别的征象。有文献报道, T2压脂像短T2信号间隔是鉴别两种肿瘤的一个关键[16], 但本研究未发现两者该征象有统计学差异, 可能与收集病例的差异性有关。有文献报道, 钙化/残留骨也是鉴别骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤的一个征象[16], 本研究亦未发现这个征象有统计学差异, 可能与病例数少有关。

总之, 本研究结果表明, 骶尾部骨巨细胞瘤和脊索瘤在病人年龄、发病部位、肿瘤的生长方式、椎旁有无软组织包块、病变累及部位、病变是否累及椎间隙、骨壳的完整性等方面存在差异, 这有助于两种肿瘤的鉴别诊断。当然本研究也有一定局限性:①样本量较小; ②病例资料不是特别完善, 所选病人只做了CT和MRI平扫检查, 没有行CT和MRI增强检查。故需要在今后的研究中增加样本量, 收集更加完善的资料, 以提供更多有价值的信息。

| [1] |

BORIANI S, BANDIERA S, CASADEI R, et al. Giant cell tumor of the mobile spine a review of 49 cases[J]. Spine, 2012, 37(1): E37-E45. |

| [2] |

SAMSON I R, SPRINGFIELD D S, SUIT H D, et al. Operative treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A review of twenty-one cases[J]. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American Volume), 1993, 75(10): 1476-1484. DOI:10.2106/00004623-199310000-00008 |

| [3] |

BORIANI S, CHEVALLEY F, WEINSTEIN J N, et al. Chordoma of the spine above the sacrum. Treatment and outcome in 21 cases[J]. Spine, 1996, 21(13): 1569-1577. DOI:10.1097/00007632-199607010-00017 |

| [4] |

DAHLIN D C. Caldwell lecture. Giant cell tumor of bone:highlights of 407 cases[J]. American Journal of Roentgenology, 1985, 144(5): 955-960. DOI:10.2214/ajr.144.5.955 |

| [5] |

CAMPANACCI M, BALDINI N, BORIANIS, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone[J]. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 1986, 5(1): 183-200. |

| [6] |

RICH T A, SCHILLER A, SUIT H D, et al. Clinical and pathologic review of 48 cases of chordoma[J]. Cancer, 1985, 56(1): 182-187. |

| [7] |

SI Mingjue, WANG Chengsheng, DING Xiaoyi, et al. Differentiation of primary chordoma, giant cell tumor and schwannoma of the sacrum by CT and MRI[J]. European Journal of Radiology, 2013, 82(12): 2309-2315. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.08.034 |

| [8] |

LUKSANAPRUKSA P, BUCHOWSKI J M, SINGHATA-NADGIGE W, et al. Management of spinal giant cell tumors[J]. Spine Journal, 2016, 16(2): 259-269. |

| [9] |

RADAELLI S, STACCHIOTTI S, RUGGIERI P A, et al. Sacral chordoma:long-term outcome of a large series of patients surgically treated at two reference centers[J]. Spine, 2016, 41(12): 1049-1057. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001604 |

| [10] |

UHL M, WELZEL T, JENSEN A, et al. Carbon ion beam treatment in patients with primary and recurrent sacrococcygeal chordoma[J]. Strahlentherapie Und Onkologie, 2015, 191(7): 597-603. DOI:10.1007/s00066-015-0825-3 |

| [11] |

ROTONDO R L, FOLKERT W, LIEBSCH N J, et al. High-dose proton-based radiation therapy in the management of spine chordomas:outcomes and clinicopathological prognostic factors[J]. Journal of Neurosurgery-Spine, 2015, 23(6): 788-797. DOI:10.3171/2015.3.SPINE14716 |

| [12] |

田爱民, 李威, 马国林. 脊索瘤的影像学诊断和鉴别诊断[J]. 实用医学影像杂志, 2013, 14(1): 38-40. |

| [13] |

KWON J W, CHUNG H W, CHO E Y, et al. MRI findings of giant cell tumors of the spine[J]. American Journal of Roentgenology, 2007, 189(1): 246-250. DOI:10.2214/AJR.06.1472 |

| [14] |

GERBER S, OLLIVIER L, LECLÜRE J, et al. Imaging of sacral tumours[J]. Skeletal Radiology, 2008, 37(4): 277-289. DOI:10.1007/s00256-007-0413-4 |

| [15] |

SI Mingjue, WANG Chenguang, WANG Chengsheng, et al. Giant cell tumours of the mobile spine:characteristic imaging features and differential diagnosis[J]. Radiologia Medica, 2014, 119(9): 681-693. DOI:10.1007/s11547-013-0352-1 |

| [16] |

TSUJI T, CHIBA K, WATANABE K, et al. Differentiation of spinal giant cell tumors from chordomas by using a scoring system[J]. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology Orthopedie Traumatologie, 2016, 26(7): 779-784. DOI:10.1007/s00590-016-1819-2 |

2019, Vol. 55

2019, Vol. 55